|

Accounting Essay :Accounting Research The Press as a Watchdog for Accounting Fraud

ABSTRACT

This paper investigates the press’s role as a monitor or “watchdog” for

accounting fraud. I find that the press fulfills this role by rebroadcasting

information from other information intermediaries (analysts, auditors, and

lawsuits) and by undertaking original investigation and analysis. Articles based

on original analysis provide new information to the markets while those that

rebroadcast allegations from other intermediaries do not. Consistent with a

dual role for the press, I find that business-oriented press is more likely to

undertake original analysis while nonbusiness periodicals focus primarily on

rebroadcasting. I also investigate the determinates of press coverage, finding

systematic biases in the types of firms and frauds for which articles are published.

In general, the press covers firms and frauds that will be of interest

to a broad set of readers and situations that are lower cost to identify and

investigate.

∗Harvard University. I thank an anonymous referee, Jeff Abarbanell, Mary Barth, Sudipta

Basu, Brian Bushee, Fabrizio Ferri, Stu Gilson, Cristi Gleason, Michelle Hanlon, Paul Healy,

Jack Hughes, Amy Hutton, Bruce Johnson, Bob Kaplan, Tom Lys, Michael Maher, Maureen

McNichols, Doug Skinner, RossWatts, GregWaymire, and JoeWeber as well as workshop participants

at Boston College, Emory University, Harvard Business School, Massachusetts Institute

of Technology, Notre Dame University, The Ohio State University, University of Iowa, University

of Michigan, University of Texas-Austin, the 2004 Duke/UNC Fall Accounting Camp, and

the 2003 Stanford Summer Camp, and several anonymous members of the press for comments

on earlier versions of this paper. I thank Sarah Eriksen, Anne Karshis, and Kathleen Ryan for

research assistance. I am grateful for the funding of this research by the Harvard Business

School.

1. Introduction

This paper examines the press’s role as an early information intermediary

in the public identification of corporate financial malfeasances. Prior

literature regarding the press is limited and presents a conflicting view of its

effectiveness as an information intermediary. On the one hand, there are

arguments that the press caters to the lowest common denominator, does

not provide in-depth research or analyses, and focuses on sensationalizing issues

in order to sell papers (Jensen [1979], Core, Guay, and Larcker [2005],

DeAngelo, DeAngelo, and Gilson [1994, 1996]). On the other hand, there

is evidence that a free media is related to country-level economic growth

and that pressure created by press coverage can play an important role in

the corporate governance of firms (Djankov et al. [2002], Dyck and Zingales

[2002a], Dyck, Volchkova, and Zingales [2005]). The later studies suggest#p#分页标题#e#

the press plays an important informational role, but do not examine how

this is achieved. While a few studies do examine the impact of specific information,

they have focused on rebroadcasting of information created by

management or other information intermediaries (Huberman and Regev

[2001], Dyck and Zingales [2003], Dyck, Volchkova, and Zingales [2005]).

Thus, even for studies that suggest the press is an important informational

source, there is limited evidence regarding how the press fulfills the informational

role and no evidence regarding whether the press provides new

information.

In this paper I use a sample of firms whose accounting was challenged

by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to examine whether

the press is involved in the early public identification of an accounting

issue. Further, I study whether the press directly identified the issue or is

rebroadcasting information provided by more traditional intermediaries

(analysts, auditors, and legal institutions). Finally, I examine whether the

press is systematically biased towards covering certain types of firms and

frauds. Combined, these analyses contribute to the literature by providing

a more complete understanding of the press’s role as an information intermediary

in financial markets.

I use accounting, auditing, and enforcement releases (AAER) to identify

a sample of firms that were sanctioned by the SEC for accounting malfeasances.

Use of AAER allows me to examine a sample of firms widely believed

to have engaged in accounting fraud and provides objective measures of the

characteristics of the fraud, such as the magnitude and nature of infractions.

Mysample consists of 263 firms that have committed a wide range of accounting

violations. I find that the press publishes articles regarding accounting

fraud prior to a public acknowledgment by the firm or SEC for 75 (29%) of

the firms.

These 75 articles indicate that the press is involved in the early public dissemination

of an accounting issue, suggesting they do fulfill an information

intermediary role. I analyze the content of the articles and use market tests to

investigate whether the press is providing “original” information to the markets

or simply rebroadcasting information provided by other information

PRESS AS WATCHDOG 1003

intermediaries. My results indicate that both occur. My first analysis examines

the sources used to support the article. Many articles indicate the press

undertook original “investigative” reporting by analyzing a mix of information,

often including publicly available documents, to create its own

allegation of accounting misdeeds. However, other articles refer to traditional

information intermediaries, such as analysts, litigation/court actions,

and auditor changes, suggesting the press treats rebroadcasting as a legitimate#p#分页标题#e#

information role. Further supporting a dual role in the press, I find

evidence that press outlets and writers that specialize in business reporting

are more likely to provide original stories, while local papers and generalists

are more likely to rebroadcast existing information.

I next examine whether the articles provide incremental information to

capital market participants. I perform this analysis by informant category: reporter

original, analysts, auditors, and law. Prior work has argued that press

coverage is important due to the pressure it places on management (Dyck

and Zingales [2002a], Dyck, Volchkova, and Zingales [2005]). If press coverage

per se is informative, I would expect a negative response to all article

categories. Since reporter-generated analysis provides new information, I

predict a greater response to such articles. I find that the response is greater

for articles based on reporter analysis than for those that rebroadcast from

other information intermediaries. After controlling for publication type,

the response to reporter investigation is approximately −12.6%, while the

response to rebroadcasting articles is not significantly different from zero.

These findings show that in many cases the press develops new information

for the markets, suggesting an important role as an independent monitor

or information intermediary in financial markets. However, it provides no

support for an informational role when rebroadcasting from other information

intermediaries. Of course, it is still possible that this rebroadcasting

plays an important role in attracting the attention of entities that may take

actions (such as regulatory or consumer groups), consistent with political

costs and monitoring suggestions in prior literature (Watts and Zimmerman

[1986], Dyck and Zingales [2002a]).1

Having established that the press plays a role in the early identification

of fraud, I examine how characteristics of the firm and fraud impact the

likelihood of an article alleging fraud. The goal of this analysis is to provide

evidence regarding when the press acts as a monitor of firms’ activities. My

predictions are based on the press trading off the long-term pecuniary cost

and benefits of acting as a watchdog.

I predict that firms with high information visibility are more likely to have

articles written regarding their accounting fraud due to the obvious high

interest in these firms, which suggests there will be interest in a story, and to

1 It is important to note that the tests are designed to exclude the period when the rebroadcasted

information was initially excluded. Thus, my findings are not suggesting that these other

sources lack credibility in general or even are less credible than the press as a source for allegations.

Rather, the results suggest that there is no incremental reaction when these allegations#p#分页标题#e#

are made broadly public through the press.

1004 G. S. MILLER

the lower cost of investigating firms with a rich information environment.

Consistent with these predictions, I find that firms with a large number of

general press articles or greater market value of equity are more likely to

have their accounting violations first identified in the press. However, I find

no evidence that greater analyst following increases the likelihood of an

article.

Audit changes are public events that draw attention to a firm. They also

provide the basis for beginning a story regarding the firm’s accounting. Due

to these reduced costs, I predict and find that articles are more likely for

firms with auditor changes.

The press industry generates much of its income from advertising revenue

and so may be less likely to be critical of firms that are currently large

advertisers or have the potential to be in the future. However, I find no

evidence that the press is less likely to write articles regarding firms in high

advertising industries.

I also expect aspects of the fraud will impact the cost of identifying the

fraud and the benefits of publishing an article. I use the AAER information

to capture several aspects of the fraud. I find a high association between

the number of individuals involved in the fraud and the likelihood of an

article, consistent with inside leaks reducing the cost of investigating frauds.

Frauds with a greater dollar magnitude are also more likely to result in a

story, consistent with coverage of more egregious and interesting frauds.

Similarly, frauds that involve public misleading statements (such as a press

release claiming a large new contract and related accounting malfeasances

to support the press release) are likely to both reduce search costs and be

of greater interest to readers of the original disclosure. Consistent with this,

I find articles are more likely if the AAER alleges the company provided

a material publicly misleading statement or filing. Finally, frauds that involve

management profiting due to insider trading, hidden compensation,

or plain theft more easily lend themselves to a personalized and controversial

spin, suggesting the press may find frauds involving such actions as

being more newsworthy. Consistent with this, I find that frauds that are

accompanied by such actions are more likely to result in an article.

The purpose of this study is to provide evidence on the role of the press as

an information intermediary. The evidence indicates that the press facilitates

earlier public knowledge of a fraud both by original investigative reporting

and broadly rebroadcasting information from other intermediaries. While

the original reporting is informative to the capital markets, rebroadcasting

is not. Further, this study shows that the press is systematically biased towards#p#分页标题#e#

coverage of high visibility firms and those with interesting frauds. Combined,

this suggests that the press can provide an important informational role, but

that its coverage is far from complete. This study combines with other early

studies on the press to begin to develop a fuller understanding of the role

of the press in financial information flows.

The evidence provided in this paper is also of interest due to the increasing

use of the press as a control variable in accounting and economic studies

PRESS AS WATCHDOG 1005

(Frost, Gordon, and Hayes [2001], Bushman, Piotroski, and Smith [2003],

Haw et al. [2003]). With a greater understanding of the press, we can more

clearly determine whether these variables effectively capture the constructs

they are meant to measure.

This paper proceeds as follows: Section 2 discusses related literature and

motivates the research question, section 3 discusses the sample selection

and collection of press coverage, section 4 provides results, and section 5

concludes.

2. Related Literature, Motivation, and Research Questions

2.1 THE PRESS IN THE INFORMATION PROCESS

Existing research on the relation between the press and commerce is

limited (Zingales [2000]). The literature that does exist often has dramatically

conflicting findings. While many of the studies suggest that the press

impacts public perception in some manner, one group of studies indicates

press coverage lacks in-depth research and tends towards sensationalism.

For example, Jensen [1979] argues that the press has become a form of

entertainment and that articles are written to appeal to the lowest common

denominator. Consistent with this, Core, Guay, and Larcker [2005] study

press coverage of compensation and conclude that the press sensationalizes

their coverage by focusing on large ex post stock gains rather than compensation

expense to the company. They conclude that this press coverage

has no impact on compensation behavior. Using a clinical study approach,

DeAngelo, DeAngelo, and Gilson [1994, 1996] suggest that simplistic press

coverage of junk bonds may have skewed economic behavior of customers

and regulators. Dyck and Zingales [2002b] suggest that the press may encourage

financial bubbles by adopting a company’s spin in return for private

information. As a group, these studies question the validity of the press as

an important information intermediary in the economy and even suggest it

may play a negative role.

In contrast, other studies suggest that the press is an important component

of the information environment in society. There is a growing literature that

uses cross-sectional variation in the national characteristics of the press to

investigate the role of the press in corporate governance, governmental

actions, and development (Dyck and Zingales [2002a], Stromberg [2002],#p#分页标题#e#

Djankov et al. [2002]). This literature generally concludes that a strong

press can have a positive impact on the political and economic makeup of

a country. This impact is presumed to be driven by the oversight function

of the press. However, these studies have not examined the mechanism

through which the press exerts this oversight.

A few studies have shown that the press shapes public opinion by packaging

and rebroadcasting information that is already available (Huberman

and Regev [2001], Dyck and Zingales [2003], Dyck, Volchkova, and Zingales

[2005]). These studies indicate that press coverage per se impacts the

1006 G. S. MILLER

public’s response to information and the action of firms being covered.

Since these studies focus on rebroadcasting of information, they do not

provide any insight regarding whether the press actively investigates and

provides original information.

The goal of this paper is to add to the literature regarding the press by

examining a highly technical situation in which the press is likely to face

varying incentives to perform an investigative role. This allows me to examine

whether the press can participate as an early information intermediary

in technical situations, whether this participation includes original analysis,

the relative informational value of original analysis and rebroadcasting, and

whether the press skews coverage of frauds consistent with a preference for

sensationalism.http://www.ukassignment.org/Accounting_Essay/

2.2 THE PRESS AS A WATCHDOG FOR ACCOUNTING FRAUD

In this paper, I focus on one aspect of press reporting—acting as a monitor

or “watchdog” for the public by assisting in the early identification of

accounting impropriety.2 The watchdog role is frequently referred to as

one of the most important functions of the press (Serrin and Serrin [2002],

Islam [2002], Djankov et al. [2002], Dyck and Zingales [2002a]). The watchdog

process often includes combining public and non-public information

with an analysis that highlights potential problems. Watchdog journalism

in business reporting is unique in that SEC filings and other publicly available

information provide a rich starting point for the process. However, the

reporter still must identify the issue, improvise to collect supporting information,

synthesize the information, frame the issues, and disseminate to the

general public (Keller [1998]).

My study investigates the pres’s role as a watchdog by examining whether

the press publishes an article alleging accounting irregularities prior to a

public admission by the company or announcement of an SEC investigation.

In some situations, the press provides the first public indication that

an accounting issues exists, serving as the original information analyzer. In

others, it may pick up indications from another information intermediary#p#分页标题#e#

and rebroadcast the information. Being the first entity to identify an accounting

issue is a clear example of a monitoring role, and likely contains

more informational value than the subsequent coverage. However, even if

the potential issue was identified by another public information intermediary,

the press can still provide an important function by publishing an

2 The term “watchdog” refers to a journalist alerting the public to an issue through press

coverage just as a canine watchdog alerts others to a danger by barking. As with many jargon

terms, “watchdog reporting” has a loose definition. All of the working definitions include the

need for critical thought and question asking and many also restrict the definition to cases in

which the reporter is one of the first entities to address an issue to the broader public. Others

expand watchdog reporting to the follow-up that occurs after an issue is initially identified.

While examination of that follow-up role would be interesting, it is beyond the scope of this

paper.

PRESS AS WATCHDOG 1007

article that synthesizes this concern with other information regarding the

firm (Dyck and Zingales [2002a]). This validates the original concern and

makes the entire story more accessible to the general public.

Accounting fraud is an important event in evaluating companies and thus

also an important news event. The often extreme actions, tensions, and personalities

involved in accounting fraud create a compelling story, consistent

with sensationalism (Jensen [1979]). For example, one popular journalism

text, Jamieson and Campbell [2001, p. 41–52], defines a “newsworthy event”

as having five characteristics: (1) can be personalized, (2) dramatic, violent,

and conflict filled, (3) actual and concrete, (4) novel and deviant, and (5)

an issue of ongoing concern. Accounting fraud is one of the few business

stories that meets all five criteria.

However, countervailing pressures may reduce the pres’s activities as

watchdogs over firms. The nongovernment-owned press are market participants

themselves. Many of their interests are aligned with the market,

making it less likely that they desire to cause concern regarding the market

or face scrutiny themselves (Herman [2002]).3 These apprehensions can be

intensified by affiliations with parent companies or advertisers who may be

harmed by investigative reporting (Herman [2002], Jamieson and Campbell

[2001]). The press also may censor stories in an attempt to keep ongoing

sources available for future information (Jensen [1979], Herman [2002],

Dyck and Zingales [2002b, 2003]). Individual reporters may be concerned

about retaining their job and/or future employability if representatives of

companies complain to their editors (McNair [2002]).4 Finally, the press#p#分页标题#e#

has to be concerned about offending its readers, who are participants in the

market themselves (Jamieson and Campbell [2001]).5 These forces suggest

that the press is likely to face strong pressure against reporting accounting

improprieties.6 Accordingly, the press may choose not to provide initial or

early information regarding the problems, but rather to wait until a fraud has

been publicly acknowledged by the company and then use ex post articles

to fulfill the need for interesting business stories.

As the above discussion shows, the watchdog role could be an important

commerce-related function of the press. However, we have no

3 Jamieson and Campbell [2001, p. 62–63] quote Peter Silverman, the business and financial

editor of the Washington Post: “Newspapers themselves are among the most secretive and the

most protective about the facts and figures of their own business. They are not likely to ask

others to do what they are unwilling to do themselves.”

4 McNair [2002] presents several examples of attempts by businesses to silence reporters.

While many were not successful, in at least one case a reporter was fired shortly after a company

complained about coverage (McNair [2002, p. 14]).

5 BillWasik, an editor of Harpers, argues “When a company’s fortunes seem poised to enlarge

indefinitely, the interests of all potential sources—the company, the analysts, large investors—

are aligned not only with one another but with the interests of the reader , who is assumed to be a

shareholder or potential shareholder.” (Wasik [2003, p. 84]) (Italics in original).

6 It is interesting to note the similarity between these forces and those studied in the analyst

and auditing literatures.

1008 G. S. MILLER

understanding of if or how this occurs. Specifically, how often does the press

participate in the early public identification of an accounting fraud? Is this

done primarily through reporter investigative analysis or as a rebroadcasting

of other information intermediaries? Does the market view either action as

informative? Is there systematic bias in the types of firms or frauds covered

in the press? The next section develops specific research predictions and

methods for each of these issues.

2.3 RESEARCH QUESTIONS

2.3.1. Press Participation in Early Allegations of Accounting Malfeasances. I

first examine the degree to which the press fulfills the early identification

role. As I discuss more fully in the data section, I include firms in my sample

based on SEC AAER that allege accounting violations.7 Examining the

proportion of these firms identified by the press prior to the official announcement

of an accounting issue provides evidence regarding the press’s

ability to identify and its willingness to publish stories regarding suspected#p#分页标题#e#

fraud.

Next, I examine whether the articles more broadly disseminate information

created by other intermediaries versus providing an original analysis

and synthesis of new information. I address these questions using both an

examination of the sources stated in the articles and a returns-based event

study. I first examine the articles and code them as either attributing the

allegations to another information intermediary (analysts, auditors, or legal

functions) or investigative analyses by the press. These investigative analyses

are based on a wide range of activities such as review of financial statements,

channel checking with customers, investigation of announced contracts, etc.

Of course, isolation of sources based on the ex post article is difficult, as the

press may initially receive information from one entity but in the process

of writing the article rely on subsequent sources. Assuming no systematic

biases in such switches, this portion of the study still should provide insight

into the process by which the press collects information.

Reporter-generated analysis of accounting is a technical skill that is more

likely to exist within specialized business publications and reporters. Thus,

I expect that reporters and publications with these skills are more likely to

generate articles with original content, while those in less specialized outlets

are more likely to rebroadcast the views of other information intermediaries.

I investigate this within-press variation by examining the relation between

sources of information in an article and type of press/reporter.

I use a market return event study as a final method of examining original

information content versus rebroadcasting of information. If the press is

7 I use the term fraud in a broad sense to imply any type of systematic accounting misstatement.

AAER are the SEC’s version of the actions that led to an accounting misstatement within

the firm. Firms settle AAER without admitting or denying guilt and thus still may argue that

they were not guilty of accounting fraud or misstatement. However, the existence of an AAER

suggests that the SEC believes there were sufficient problems to make a public case.

PRESS AS WATCHDOG 1009

playing an informative role there will be a negative reaction to the articles.

Conversely, if the press is simply repeating widely known information and/or

is not considered a reliable source of analysis, then there will be no reaction

to the articles. Based on this, in the cross-section I expect a larger reaction

to articles that rely on reporter-generated information than on those that

rebroadcast information from other intermediaries. Several studies argue

that the press changes expectations and actions by rebroadcasting information

(Huberman and Regev [2001], Dyck and Zingales [2003], Dyck,#p#分页标题#e#

Volchkova, and Zingales [2005]). Consistent with these studies, I expect a

negative reaction even for rebroadcasted articles.8

2.3.2. Characteristics of Firms and Frauds That Influence the Likelihood of an

Article. The press may be an effective monitor in some situations, but ineffective

in others due to biases in coverage (Mullainathan and Shleifer

[2002]). Thus, I examine the firm and fraud characteristics that lead the

press to identify and publish an allegation of accounting fraud in some instances

while missing or staying silent in others. As with all economic agents,

I expect reporters will choose articles based on maximizing benefits and reducing

costs. That is, the press prefers articles that are interesting to a large

group of readers, resulting in higher subscription revenues and a larger

reader base to offer potential advertisers (Stromberg [2002]). Further, the

press will attempt to increase future readership by publishing stories readers

find memorable (Mullainathan and Shleifer [2002]). The press must also

consider the cost of undertaking such investigations. Firms with a richer information

environment can be analyzed more easily and some aspects of the

frauds may be easier to detect, both of which reduce the cost of investigation.

As is often the case, it is difficult to separate the impact of cost and benefits

in much of my empirical analyses. Accordingly, I discuss the empirical

implementation of the predictions provided by costs and benefits together.

I begin by considering three firm-level characteristics.

I expect that firms with a high number of stakeholders present an opportunity

to attract a large reader base. Further, stakeholder demand for

information should lead to greater demand for information directly from

the firm and an increased number of other information intermediaries following

the firm, resulting in a richer information environment for these

firms. Thus, relative to other firms, the benefits of coverage of these highvisibility

firms are greater and the cost of analyzing these firms is lower. I

proxy for high visibility by using market value, analyst following, and overall

press coverage (details of these items are discussed more fully in the sample

and results sections).

8 Dyck and Zingales [2002a] and Dyck, Volchkova, and Zingales [2005] are more in the

spirit of studying the impact of a group of articles rather than a single article. Accordingly, my

study of individual articles does not directly address their monitoring hypothesis. Instead, it

examines whether rebroadcasting creates an immediate informational update.

1010 G. S. MILLER

Auditors are primary analyzers of firm financial information. Changes in

auditors may serve to draw attention to a firm’s accounting and even provide

leads to disputed accounting issues. This reduces the cost of investigating#p#分页标题#e#

the firm. Thus, I expect that firms that experience an auditor change are

more likely to receive an article.

A firm’s advertising spending also may impact the likelihood of a critical

article. Advertising is an important source of revenue for the press and

publishers may be hesitant to print articles that will offend large current

or prospective advertisers (Reuter and Zitzewitz [2003]). Articles alleging

inappropriate accounting have a high potential for upsetting affected advertisers.

I predict firms that have the potential to be large advertisers are less

likely to be the subject of unfavorable articles. I proxy for advertising status

using an indicator variable that is coded as 1 if the firm is in an industry

that was in the top 15 advertising industries (according to Advertising Age)

in each of 1985, 1990, 1995, and 2000.

Next, I expect that characteristics of the fraud may impact the press’s

ability to frame the story in a way that will appeal to a broad set of readers

and/or the ease with which the press can detect the fraud. Thus, these

characteristics will influence both the costs and benefits that determine

whether an article is written regarding a particular fraud. I use information

from the AAER to collect various aspects of the fraud.9

By nature, frauds are designed to be concealed from outsiders. Thus,

identification of a fraud can be costly and the outcome highly uncertain at

the beginning of an investigation. An internal leak, or at least indication

of the potential for an issue, can have a strong influence on reassuring the

reporter that there is a story to be pursued and may even point the reporter

towards the sources needed to confirm the fraud. The more people involved

in the fraud, the greater the likelihood of a leak of the activities to outsiders.

Accordingly, I predict that the likelihood of an article is increasing in the

number of people involved in the fraud.

Frauds that involve a large dollar magnitude may be deemed as more

newsworthy, increasing the benefit of publishing an article. I investigate

whether the dollar magnitude of the fraud is related to the likelihood of an

article by including the total magnitude of the fraud.

I expect the press to be more likely to identify a fraud that involved a

materially misleading public statement. Such statements are likely to attract

scrutiny and communicate items the company expects will catch the

public’s attention, suggesting broad appeal to consumers of the press. Further,

they allow the reporter to frame the story as having caught management

attempting to fool the public, creating a personal element as well as

showing conflict and deviant behavior. This item both increases the benefits

and decreases the costs of investigating and publishing a story on the

firm.#p#分页标题#e#

9 The SEC often publishes multiple AAER regarding a single infraction. I collected information

from all AAER when this occurred. Given the difficulties in identifying AAER, it is possible

that some AAER were missed, introducing noise into the tests.

PRESS AS WATCHDOG 1011

Many accounting frauds occur concurrent with management misappropriation

of funds, either through illegal insider trading, manipulation of

bonus plans, or pure theft. While the cost of identifying these actions is unclear,

they will make the story more compelling by increasing the degree to

which the article can be personalized, is dramatic, has conflict, and covers

deviant behavior.

3. Research Design and Sample

3.1 SAMPLE CREATION AND AAER

To investigate the press’s actions as a watchdog for accounting malfeasances,

I must identify firms that have committed accounting violations.

Consistent with prior work, I use the SEC AAER to build a sample (Dechow,

Sloan, and Sweeney [1996], Bonner, Palmrose, and Young [1998], Beneish

[1999a, b]). There are differing opinions regarding why AAER are issued.

While some believe they are meant to address current trends observed by

the SEC (Feroz, Park, and Pastena [1991]), others believe they are issued

for high-profile cases that will enhance the stature of the SEC (DeFond and

Smith [1991]). In any case, there is wide agreement in the literature that

AAER generally represent egregious violations of the generally accepted accounting

principles (GAAP) standards of reporting and disclosure. As such,

they provide the basic criteria needed to develop my sample: an observable

sample of firms that have committed accounting malfeasances. AAER have

the added advantage of providing detailed information, such as discussion of

the violations, summaries of findings, and a timeline of the violation. This

in-depth characterization is helpful in developing variables to investigate

how the type of fraud impacts press coverage.

Use of AAER has disadvantages. First, AAER likely represent extreme

violations. If these firms have characteristics that vary systematically from

firms that commit fraud but do not receive an AAER, then the results may

not generalize into the population in general. Second, Feroz, Park, and

Pastena [1991] report that an SEC official indicated that approximately

one-third of its leads come from the financial press. It is not clear whether

that entails only articles that allege fraud, or that the press is simply one

source for collecting information. However, it is possible that a portion of

these firms would not have been identified without the press. Assuming

that all such articles are read by the SEC and that the SEC would never

identify the fraud absent press coverage, the findings in this paper would

likely overstate the proportion of frauds in the general population that are#p#分页标题#e#

identified by the press. That is, there may be many frauds missed by both

the SEC and the press.

AAER are identified using the SEC Web site.10 AAER are issued for a

wide range of violations. While accounting fraud is a primary reason for

10 As a robustness check, the AAER identified were compared to those in the October 2002

General Accounting Office document Financial Statement Restatements, Trends, Market Impacts,

Regulatory Responses , and Remaining Challenges. There were no discrepancies noted.

1012 G. S. MILLER

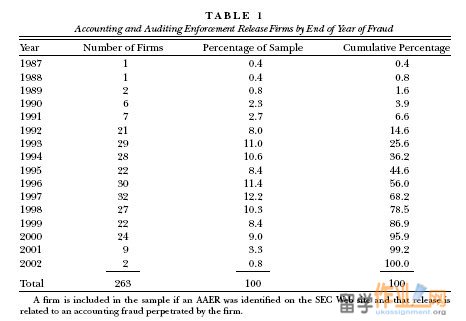

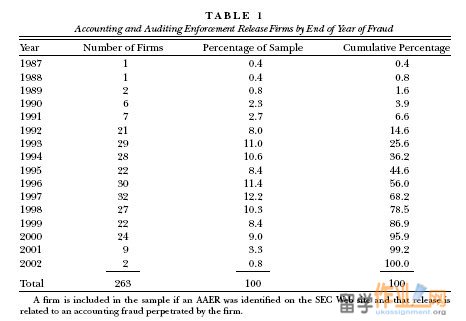

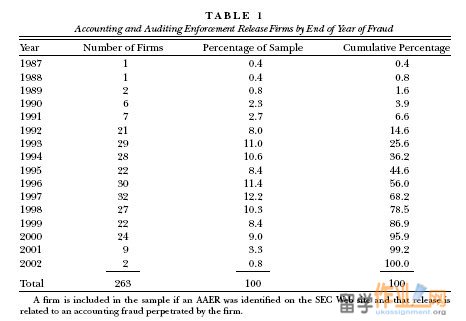

TA B L E 1http://www.ukassignment.org/Accounting_Essay/

Accounting and Auditing Enforcement Release Firms by End of Year of Fraud

Year Number of Firms Percentage of Sample Cumulative Percentage

1987 1 0.4 0.4

1988 1 0.4 0.8

1989 2 0.8 1.6

1990 6 2.3 3.9

1991 7 2.7 6.6

1992 21 8.0 14.6

1993 29 11.0 25.6

1994 28 10.6 36.2

1995 22 8.4 44.6

1996 30 11.4 56.0

1997 32 12.2 68.2

1998 27 10.3 78.5

1999 22 8.4 86.9

2000 24 9.0 95.9

2001 9 3.3 99.2

2002 2 0.8 100.0

Total 263 100 100

A firm is included in the sample if an AAER was identified on the SEC Web site and that release is

related to an accounting fraud perpetrated by the firm.

an AAER, they also frequently include insider trading, violations of SEC

requirements by auditing firms, and other illegal acts. For the purposes

of this study, only AAER that include a substantial accounting fraud are

retained.11 Subsequent analyses rely heavily on data from the Factiva news

service, such as identifying the date a firm issues a press release that it is

under investigation or restating earnings. The two primary services for firm

press releases are PR Newswire, with coverage beginning January 2, 1985 and

Business Wire, with coverage beginning July 28, 1998. Accordingly, AAER

with violation periods that began prior to January 2, 1985 are excluded.12 As

shown in table 1, this results in a sample of 263 AAER with violation periods

ending between 1987 and 2002.13

Information from eachAAERis coded for use in subsequent tests. Untabulated

analyses show that the AAER in this sample are consistent with those in

prior studies. For example, revenue manipulation is the most common form

of violation (49% of the sample) (Feroz, Park, and Pastena [1991]). Asset

overstatement is the second most common violation (35% of the sample).

11 For example, there were several AAER that involved payments that violated the Foreign

Corrupt Practices Act. These AAER also noted minor accounting violations related to how the#p#分页标题#e#

payments were recorded.

12 Robustness tests indicate the results are similar if AAER with violation periods prior to

July 28, 1998 are excluded.

13 The number of frauds in the beginning years of my study is low due to the requirement

that the fraud occur no earlier than 1985 and the generally long lag time between a fraud and

AAER. Similarly, the number of frauds in the last two years of my study is low due to the same

lag and the data collection period in early 2003.

PRESS AS WATCHDOG 1013

Other common violations include providing materially misleading public

statements/filings (26%) and manipulation of reserves (18%). These sum

to greater than 100% because the SEC frequently identifies more than one

violation per firm. In fact, the number of violations noted in the AAER vary

from one (16% of the sample) to seven or greater (1% of the sample).14

3.2 PRESS COVERAGE

Coverage is collected over several time periods, with searches designed to

create different variables. All press searches are performed on Factiva, which

is Dow Jones’s replacement for the Dow Jones News Retrieval service. Factiva

covers nearly 8,000 sources of information including all of the major wire

services (e.g., PR Newswire, Business Wire, Dow Jones, Rueters, AP), major

U.S. business publications (The Wall Street Journal, Barron’s, Forbes, Fortune,

Business Week), national and regional newspapers (The New York Times, Washington

Post, Los Angeles Times, St. Petersburg Times), and trade publications

(Computergram, Boating Industry).15

The first search examines press coverage over the period that the accounting

fraud occurred (i.e., the infraction period). This information is used to

assess the intensity with which the press examined the firm while the fraud

was occurring. Searches are performed using multiple variations of the firm

name within one search (full and corporate diminutives). Because the goal

is to identify press coverage, the wire services that directly reprint managerial

news releases (PR Newswire and Business Wire) are excluded from this

search. Similarly, summaries of a list of firm names and an item (such as

a large traded volume during the day) are excluded.16 Searches cover the

entire text of all documents. The resulting number of press articles is then

deflated by the length of the infraction period (in months) to standardize

press coverage across firms.17 The untabulated distribution of the number

of articles per month varies, with 42 of the firms averaging one or fewer articles

a month, and 18 included in more than 100 articles per month during

the infraction period. However, most firms have between 2 and 20 articles

per month.

I search for articles that identify the accounting fraud from the beginning

of the infraction period until the date of AAER issuance. However, articles#p#分页标题#e#

14 As a robustness check, all variables are interacted with the year of the violation to assure

there are no trends over time that may impact the use of these variables in later analyses. No

such trends are noted.

15 As a robustness check, several firms are randomly selected and press searches are run on

Factiva, Dow Jones, and LexisNexis. The results find Factiva to be a superset of Dow Jones.

While a few items appear on LexisNexis that were not on Factiva, they are not from major

publications and do not include information excluded by sources on Factiva.

16 These summaries include the DJ Highlights, News Highlights, V-Alert, P-Alert, California

Summary, Southeast Summary, Southwest Summary, Dow Jones Corporate Economic News

Summary, Recap of Dow Jones Special Reports, The Wall Street Journal Earnings Summary, and

the International Calendar of Corporate Events.

17 All reported results are similar if the undeflated variable is used.

1014 G. S. MILLER

are excluded if written after a public announcement by the firm of either an

SEC investigation or accounting restatement. There are often several years

between the infraction period and issuance of the AAER so a search string

is designed to comprehensively identify articles that question the firm or its

accounting while reducing the number of spurious articles to be read.18 If an

article is identified, only the first article is retained. Data on that article are

collected, including the publication, author, type of article, and cited source

of information. The decision of whether an article “caught” an accounting

failure is obviously judgmental.19 Coding bias was avoided by employing a

research associate who was not aware of any of the hypothesized relations.

In the case of uncertainty, a second research associate reviewed the article.

4. Results

4.1 ANALYSES OF FREQUENCY AND SOURCES OF ARTICLES WRITTEN

The first analysis examines the proportion of firms the press identifies

as having questionable accounting. Table 2 shows that 75 of the 263 firms

(approximately 29%) are identified by the press prior to the SEC or firm’s

public announcement. An interaction of the percentage of firms caught

and the last year of the fraud finds no discernable pattern. Thus, the press’s

actions as a watchdog of accounting fraud appear to have remained constant

over the time of my study.

It is possible that the press frequently writes negative articles regarding

firms’ accounting and thus the 29% finding is consistent with the level of

press questioning of all firms. In that case, the press’s inability to sort out

malfeasances from legitimate accounting reduces their value as monitors.

18 The search includes both the formal and shortened versions of the firm name appearing

in the same paragraph as any variation of: accounting, audit, fraud, illegal, illicit, insider#p#分页标题#e#

trading, investigate, overstate, understate, probe, quit, quits, quitting, resign, restate, revenue,

revenue recognition, rumor, law and suit within two words of each other, opinion and withdraw

within three words, short and sell or stock within three words. It also included the company

name and any words from the following group: adjustment, compensation, doubt, dubious,

financial, number, officer, recognition, record, reserve, Securities and Exchange Commission,

and SEC combined with any words from this group: corrupt, conceal, credible, debacle, deteriorate,

difficult, discrepancy, dishonest, failure, false, falsify, fear, improper, inconsistent, ills,

irregular,misappropriate, mislead, misrepresent, negative, offense, question, sell-off, shortfalls,

skeptic, suspicious, trouble, unexpected, unsupported, violated, weak, woe, worried, and writeoff.

Several companies with no caught article identified by the primary search are searched

without the limiting string. No additional caught articles are found.

19 In fact, even the press cannot agree on whether a specific article effectively identifies

misdeeds at a firm. For example, in the summer 2002 Neiman Reports there are three articles

regarding press coverage of Enron. Madrik [2002] contends that reporters did not look skeptically

at Enron, and in fact helped to perpetuate many of its practices. On the other hand, Behr

[2002] argues that negative coverage was minimal, but points to a March 2001 Fortune article

as raising questions regarding Enron. Steiger [2002, p. 10] (a managing editor at The Wall

Street Journal) argues that Enron’s misdeeds were uncovered in October of 2001 by “relentless,

careful, intelligent work of two Wall Street Journal reporters.”

PRESS AS WATCHDOG 1015

TA B L E 2

Firms “Caught” by Press Article Presented by Last Year of Accounting Fraud

Number of Number of Firms Percentage of Current

Year Firms with “Caught” Article Year with “Caught” Article

1987 1 1 100

1988 1 0 0

1989 2 0 0

1990 6 1 16.7

1991 7 1 14.3

1992 21 4 19.1

1993 29 9 31.0

1994 28 12 42.9

1995 22 10 45.5

1996 30 9 30.0

1997 32 7 22.0

1998 27 6 22.2

1999 22 5 22.8

2000 24 6 25.0

2001 9 3 33.3

2002 2 1 50.0

Total 263 75 na

Percent of Total 100% 28.5%

A firm is included in the sample if an AAER was identified on the SEC Web site and that release is

related to an accounting fraud perpetrated by the firm. A firm is considered “caught” by the press if an

article appears questioning the firm’s accounting prior to public disclosure by the firm (or SEC) that an

accounting problem exists.

To address this issue, 75 firms are randomly identified from the Center

for Research in Securities Prices (CRSP) database. The only criteria imposed#p#分页标题#e#

are that the year matches the time frame of the AAER sample and

that the firm continues to exist for at least two years after the initial year

of inclusion. The same research associate employs the identical search

string used for the AAER firms over a two-year period, finding only one

article alleging accounting malfeasances.20 A χ2 test indicates this rate of

1.3% is significantly lower than the 29% found in the AAER sample (0.001

level).

Next, I use the information in articles alleging fraud to gain a better understanding

of whether the press generates original information or primarily

rebroadcasts views of other intermediaries. Table 3, panel A classifies articles

into source categories meant to aggregate articles that suggest a similar

underlying information-gathering process: reporter-generated information,

analyst, legal cases, and auditor resignations. Articles in the first category

suggest the press is the first information intermediary to publicly identify

the accounting issues. Articles in the last three categories make it more likely

20 A second article is identified that the research associate does not believe alleges fraud,

but does challenge the explanation of legitimate accounting provided by the company. If it is

included as an article, the rate increases to 2.7% and the difference with the AAER sample is

still statistically significant at the 0.001 level.

1016 G. S. MILLER

TA B L E 3

Information Sources and Types of Publication for Watchdog Articles

Panel A: Information sources cited by the press

Number of Percentage of Cumulative

Information Source Articles Caught Sample Percentage

Reporter-generated information 27 36.0 36.0

Analyst 22 29.4 65.4

Legal cases 15 20.0 85.4

Auditor resignation 11 14.6 100.0

Total 75 100 100

Panel B: Types of publications

Number of Percentage of Cumulative

Type of Publication Articles Sample Percentage

National business 29 38.7 38.7

Local market 23 30.7 69.4

Electronic business 14 18.7 88.1

Trade publications 7 9.3 97.4

National nonbusiness 2 2.6 100

Total 75 100 100

Source is based on the source that is attributed as providing the primary information or to have

provided the information that initiated the article. Reporter-generated information includes articles that

state sources as publicly available SEC documents or financial statements, analysis of public statements

made by the firm, tips from customers, industry insiders, or anonymous sources, or article is written based

on analysis from such information without stating another external source. Analyst includes attribution to

an individual who is a sell-side analyst or buy-side analyst, to a professional investing newsletter, or to short

sellers (named or anonymous). Legal cases include articles that reference information either from court#p#分页标题#e#

proceedings or from participants in court proceedings (civil and criminal). Auditor resignations references

8-K are of auditor changes. Industry/customer information includes attribution to either industry insiders

or customers of the firm (named or anonymous).

National business publications are publications that cover the national (or global) areas. This category

includes The Wall Street Journal, Fortune, etc. Local market publications are generally regional papers,

such as The San Francisco Chronicle, Chicago-Sun Times, etc. Electronic business publications consist almost

entirely of the Dow Jones News Service with one article from Bloomberg. Trade publications are based

on covering a specific industry in depth. Examples include Boating Industry and Business Insurance. The

national nonbusiness publications are USA Today and The New York Times.

that the press is not the first to provide identification, but rather played the

more limited role of rebroadcasting. Still, this highlighting of an issue is an

important function in the overall watchdog process.

Articles based on reporter-generated information are most common, with

27 articles (36% of the sample). This includes articles using reporter-based

analysis of public information (such as financial statements) and articles

relying on information from sources that are not normally available to the

general public (such as customers or industry insiders).21 In each of these

articles, it is the reporter making the case for accounting impropriety based

21 Many of these articles simply refer to the financial statements without providing exact

sources (i.e., they just say the latest quarter or annual report). However, others provide a

detailed explanation of the information used. As a few examples, seven of the articles refer to

customers or industry insiders, two to anonymous tips, one to Web-based information, four to

specific SEC filings (by filing number and page), etc.

PRESS AS WATCHDOG 1017

on analysis of public and private information. No other information intermediaries

(i.e., analysts, auditors, or the legal system) are cited.22 Many of

these articles provide a clear description of press-initiated investigative reporting,

but others question the accounting without discussing the reason

for investigating the firm.23

Analysts are referenced in 22 articles (29%), making them the second

most common source. In most cases, it is difficult to determine whether such

articles are the result of press-initiated discussion of the firm or if the analyst

identified the issue and took it to the press.24 Limited information in the

articles suggests both occur.25 Only 8 of the articles refer to written analyst

reports (3 sell side, 5 newsletters), while 10 articles identify the analysts as

working for the buy side/shorts who would not generally provide public#p#分页标题#e#

reports. The private nature of these entities indicates that the press is the

likely vehicle for bringing many of these allegations to the general public.

To further understand the relationship between analysts and the press, I

compare fraud identification rates and sources for firms with sell-side coverage

to those without (per I/B/E/S). Thirty-six of the 133 firms with no

coverage are identified in an article (27%), while 40 of the 130 firms with

analyst coverage are identified (31%). These amounts are statistically equivalent.

Turning to the sources of coverage, analysts are cited in only 7% of

the articles for firms without sell-side coverage, but in 43% of the articles

for firms that have sell-side coverage. Conversely, 47% of the articles for

the noncovered firms are based on reporter analyses, compared with only

28% of those for firms with coverage. It is possible that the high number of

reporter-generated articles is indicative of the actual proportion of articles

that are press initiated and the analysts’ cites are simply an attempt to use

analysts as third-party “experts” in a press-identified article. Alternatively,

the shift in percentage could indicate that the press is more likely to undertake

independent analyses in the absences of analysts’ coverage. In either

case, it indicates that the press is capable of identifying a large proportion

of articles without analysts’ support.

22 If an analyst, lawsuit, or auditor resignation was mentioned, the article was classified in

that related category regardless of the extent of additional analysis provided.

23 As an example of articles that indicate press-initiated investigative reporting occurred,

a reporter noticed an ad to sell specialized used computer equipment as part of liquidating

a line of business. No company was identified, but there was a local (Silicon Valley) number.

The reporter called the number and asked what company he had reached. He investigated

the company and found they had made several recent public statements regarding the strong

performance of that sector of their business with no mention of liquidation.

24 I attempt to search for analyst reports that alleged accounting malfeasances prior to the

publication of a press article. However, it is difficult to obtain analyst reports over much of the

period of the study.

25 Anecdotal discussion with analysts and reporters also suggests both happen. Several analysts

have indicated the press as an important ongoing source of information. Further, analysts

indicated they are frequently contacted by the press regarding companies they do not follow

or follow “passively.”

1018 G. S. MILLER

The third most frequently cited source is legal cases, which occur in 15

(20%) of the articles. They range from shareholder lawsuits alleging malfeasance#p#分页标题#e#

to civil cases involving wrongful discharge and criminal cases investigating

theft. It is easy to determine causality in legal cases as the filing leads

the reporter to investigate the company. Some articles appear to rely entirely

on case information, but most articles include additional investigative

reporting such as speaking to officers or customers of the company.

The final category is auditor changes, cited in 12 (16%) of the articles.

Similar to the legal cases, the reporters use the change as a cue to look more

carefully at the company and then develop information for articles that goes

beyond that found in the 8-K filings with the SEC.26

Next, I examine the type of publications that print articles alleging inappropriate

accounting. Given the technical nature of accounting fraud, I

expect that publications that specialize in business reporting are more likely

to have the tools to identify fraud and a subscriber base that will find such articles

newsworthy. Untabulated analyses find that the articles are published

in 40 different outlets from 54 authors. The Wall Street Journal and Dow Jones

News Service have the greatest number of publications, with 14 each, followed

by The San Francisco Chronicle, with 6.27 While several publications have

multiple articles, the majority have one. Only one author has more than one

article (Herb Greenberg, who accounts for five of the San Francisco Chronicle

articles); 18 of the articles do not have an author in the byline.

Classifying publication type is inherently subjective (Jamieson and

Campbell [2001]). With this caveat in mind, table 3, panel B provides aggregated

information regarding the types of publications that cover accounting

fraud. Twenty-nine of the articles are published in national business publications

(The Wall Street Journal, Business Week, etc.). Twenty-three are from

“local market” publications (Chicago Sun-Times, Miami Herald, etc.). Fourteen

of the articles are from electronic media (Dow Jones News Service and

Bloomberg). Seven are from trade publications (Boating Industry, Business Insurance,

etc.). Finally, two are from nonbusiness national publications (USA

Today and The New York Times).28 Consistent with my expectations, these

descriptive data show the importance of business publications in serving as

26 I include analyst following and auditor change as firm characteristics in the cross-sectional

study of attributes that impact the publication of an article. I planned to include legal cases,

but a pilot search of 14 firms (5% of the sample) found that all but one had legal cases during

the period of the fraud. These cases are so common that there is effectively no variance.

27 These two sources are related. Dow Jones News Service has over 20 regional offices that

prepare articles that go out on the Dow Jones Wire Service. The articles are also submitted to#p#分页标题#e#

the editors of the The Wall Street Journal who determine whether some version of the article

should appear in The Wall Street Journal (Thompson, Olsen, and Dietrich [1987]).

28 Factiva provides limited coverage of The New York Times during some portions of my sample

period. Thus, the number of New York Times’ articles may be understated. As a robustness check,

a research assistant uses LexisNexis to search 10 companies for which no article was found and

10 companies with an article from a publication other than The New York Times. No articles were

found.

PRESS AS WATCHDOG 1019

TA B L E 4http://www.ukassignment.org/Accounting_Essay/

Relation between Sources of Information and Characteristics of the Publications

Panel A: Relation between sources of information and type of publication

National Local Electronic Trade

Information Source Business Market Business Publications

Reporter-generated information 12 8 3 4

Analyst 12 4 6 0

Legal cases 2 8 4 1

Auditor resignation 3 5 1 2

χ2 (p-value) 15.15(0.0869)

Panel B: Relation between sources of information and frequency of article

Percentage Percentage of

of Recurring One One-Time

Information Source Recurring Sample Time Sample

Reporter-generated information 10 55.6 17 29.8

Analyst 7 38.9 15 26.3

Legal cases 1 5.56 14 24.6

Auditor resignation 0 0 11 13.5

Total 18 100 57 100

χ2 (p-value) 12.20(0.0067)

Source is based on the source that is attributed as providing the primary information for or to have

initiated the article. National business publications are publications that cover the national (or global)

areas. This category includes The Wall Street Journal, Fortune, etc. Local market publications are generally

regional papers, such as The San Francisco Chronicle, Chicago-Sun Times, etc. However, for the purposes of

this table, they also include the two national nonbusiness publications (The New York Times and USA Today).

Electronic business publications consist almost entirely of the Dow Jones News Service with one article

from Bloomberg. Trade publications are based on covering a specific industry in depth. Examples include

Boating Industry and Business Insurance. Recurring articles are from a column that is published by a single

reporter/set of reporters on a regular basis. χ2 is based on a likelihood ratio χ2.

watchdogs for accounting fraud, but they also show that many other sources

uncover and publish articles regarding accounting fraud.

Next, I examine relations between the sources and types of publications.

The goal in this interaction is to examine whether the specialization of

business reporters leads to more articles based on the original (or “investigative”)

reporting interaction with other information intermediaries. To

reduce dimensionality, I combine national nonbusiness publications with#p#分页标题#e#

local market publications, as both are general interest news outlets.

Table 4, panel A shows that reporters from all publication types use a

wide variety of sources to identify accounting fraud. However, there are

patterns in the relative usage of sources consistent with specialization leading

to more active reporting. First, the national and electronic business

publications have a high reliance on analysts, while local market and trade

publications rarely use that source. Second, national business publications

rely equally on reporter analysis and analysts (12 articles from each), but do

not appear to write articles in response to lawsuits and auditor resignations,

suggesting they focus on original analysis rather than rebroadcasting legal

and regulatory filings. The χ2 value of 0.09 indicates that these differences

are statistically significant.

1020 G. S. MILLER

Panel B compares authors with a recurring column with articles that appear

as one-time coverage. Recurring authors may be more focused on providing

individual analysis, and thus developing the brand of their column.

Additionally, they are more likely to be business specialists. Accordingly, I

expect recurring authors to be more likely to rely on active reporter investigation.

The findings in panel B support this hypothesis, with the majority

of the recurring articles being based on reporter analysis while nonrecurring

articles are more likely to rebroadcast. A χ2 test finds these levels to

be significant at the 0.007 level. Combined, the source differences across

publication and author type indicate that specialization allows reporters to

develop a skill set and contacts that assist in providing original information.

The final investigation of the source of the news employs market returns to

examine whether the market views the articles as providing new information.

The market should respond negatively to new information alleging accounting

malfeasances. The prediction is less clear for rebroadcasted information.

Some studies indicate the press impacts perceptions by rebroadcasting information

(Huberman and Regev [2001], Dyck and Zingales [2003], Dyck,

Volchkova, and Zingales [2005]). On the other hand, in an efficient market,

repeating known information should not impact returns. This event-study

faces several threats to its validity. First, the day on which the article became

available is difficult to determine. This threat is relatively limited for wire

services (which report real time) and newspapers (which generally are published

in the morning, or at least available before trading ends). Magazines,

however, are frequently published in advance of the “issue date.” Difficulties

in identifying the exact date the article became public introduce noise

and reduce the power of the tests. Second, some articles cite relatively recent#p#分页标题#e#

events, such as lawsuits and auditor changes, that likely impact returns.

If these events occur within the return window used for the event study,

then results may be biased in favor of finding a market reaction. To reduce

this bias, tabulated analyses rely on one-day returns, rather than the standard

three-day window. Third, my sample of 60 firms divided into multiple

categories results in relatively low-power tests, creating some problems in interpreting

nonsignificant results. Finally, these tests only examine whether

the market treats this as new information. It is possible that this information

is already in price, but that rebroadcasting is still informative to other firm

stakeholders.

I am able to identify clean returns data for 60 of the articles using a

combination of CRSP, Datastream, and Bloomberg.29 Untabulated univariate

results find an average (median) one-day market adjusted reaction of

−6.3% (−2.9%). The same measure for the three-day return centered on

29 I identify 63 of the firms on these databases. However, two firms had significant events

announced after trading ended the day before the article and one was a penny stock trading

at $0.08 per share. If these firms are included, the results are similar except the returns for

articles based on auditor changes are significant in some specifications.

PRESS AS WATCHDOG 1021

article publication date is −8.2% (−4.5%).30 All of these amounts are statistically

significant. This evidence indicates that these articles provide new

information to the market.31

Table 5 reports regressions of day zero abnormal returns on the source,

publication, and recurrence of author, consistent with the categories in

tables 3 and 4. This analysis examines whether differences in the sources

used to write the article, venue of publication, or type of author impact

the informativeness of the article. All regressions suppress the intercept

and include indicator variables for each category. In the first three regressions,

categories are mutually exclusive, thus the coefficient is equivalent to

a mean.32 As shown in the final regression, the regression specification has

the advantage of including controls for venue and recurrence.

The first regression shows the response to articles based on source of information.

The response is statistically negative for articles based on reportergenerated

analysis or analysts. I expect reporter-generated articles, which

are based on analysis and/or sources not commonly available to the public,

to have the greatest incremental information content for the market. Consistent

with this, the −13.9% reaction to these stories is statistically greater

than that for the articles based on any of the other sources. In this specification,

articles citing analysts are also significant, though the −4.5% return#p#分页标题#e#

is both statistically and economically smaller in magnitude than the returns

for reporter-generated articles.

Table 6 also shows the response to articles in different press outlets. I

expect that business-related press outlets are more likely to provide informative

articles due to both their original reporting sources and their sophisticated

audience. Consistent with this expectation, articles in the two

business-focused outlets (wire services and national business publications)

generate a statistically negative response, while those in the other publications

are indistinguishable from zero. The other finding of note in this

regression is the much greater magnitude of the response to stories from

the wire services (−12.6%) than to those from the other publication outlets.

This is consistent with the timeliness of wire coverage providing useful

information to sophisticated market participants.

The third regression compares the response to articles from a recurring

column with those from nonrecurring authors. Again, I expect that

30 The greater magnitude for the three-day response is consistent throughout the market

tests. The relative magnitudes across categories remain consistent with the one-day measure.

However, many of the statistical significance levels are weaker, suggesting that the inclusion of

the three-day period introduces noise.

31 As an alternative explanation for unconditional market response, it may be that press

coverage imposes costs on a firm even if the underlying information is already known (such as

potential litigation issues, stakeholder communication issues). In that case, there would be a

negative response to all articles and no differential response across categories as all categories

involved press coverage.

32 Untabulated tests of medians show similar patterns of returns and levels of significance

to those in the mean/regression tests.

1022 G. S. MILLER

TA B L E 5

Regression of Day Zero Abnormal Returns on Categories of Sources, Publications, and Recurring Articles

F -Value F -Value

(p-Value) (p-Value)

Compared to Compared to

Coefficient Reporter Coefficient Coefficient Coefficient Reporter

Category (p-Value) Generated (p-Value) (p-Value) (p-Value) Generated

Reporter-generated −13.9% −12.6%

information (0.0001) (0.0004)

Analyst −4.5% 4.45 −2.2% 5.69

(0.0716) (0.0197) (0.2808) (0.0103)

Legal cases −1.7% 5.38 1.4% 7.25

(0.3376) (0.0120) (0.3753) (0.0047)

Auditor resignation 0.5% 5.28 1.9% 5.40

(0.4595) (0.0127) (0.3591) (0.6876)

National business −6.3%

(0.0247)

Local market −4.3%

(0.1317)

Electronic business −12.6% −11.0%

(0.0011) (0.0051)

Trade publications −0.4%

(0.4661)

Recur −5.1% −1.5%#p#分页标题#e#

(0.0079) (0.3611)

Nonrecur −6.7%

(0.0040)

Abnormal returns are the firm market returns per CRSP, Datastream, or Bloomberg on the day the article is released less the CRSP market returns on the same day. Returns data were identified

for 60 firms. All variables are 0/1 indicators. Source is based on the source that is attributed as providing the primary information or to have initiated the article. National business publications are

publications that cover the national (or global) areas. This category includes The Wall Street Journal, Fortune, etc. Local market publications are generally regional papers, such as The San Francisco

Chronicle, Chicago-Sun Times, etc. However, for the purposes of this table, they also include the two national nonbusiness publications (The New York Times and USA Today). Electronic business

publications consist almost entirely of the Dow Jones News Service with one article from Bloomberg. Trade publications are based on covering a specific industry in depth. Examples include

Boating Industry and Business Insurance. An article is considered regional if it is from a local publication in the same region or a national publication but provides a byline indicating the story was

written locally. Recurring articles are from a column that is published by a single reporter/set of reporters on a regular basis. As all articles are predicted to have a negative market response,

p-values are one-sided.

PRESS AS WATCHDOG 1023

TA B L E 6

Cross-sectional Examination of Characteristics of Firms and Fraud That Lead to an Article by the Press

Panel A: Means and medians

p-Value of

Variable Caught Not Caught Difference

PRESSINT Mean 51.72 24.15 0.031

Median 8.23 5.11 0.062

ANALYST Mean 0.33 0.22 0.033

Median 0 0 0.033

MV Mean 12.6 11.8 0.014

Median 12.5 11.7 0.048

AUDITOR Mean 0.40 0.28 0.0316

Median 0 0 0.0317

BIGADS Mean 0.14 0.18 0.281

Median 0 0 0.286

NUMINV Mean 4.3 3.2 0.004

Median 4 3 0.016

AMOUNT Mean 3.00 2.06 0.001

Median 2.78 2.04 0.002

MISLEAD Mean 0.37 0.22 0.008

Median 0 0 0.005

STEAL Mean 0.33 0.20 0.018

Median 0 0 0.012

Panel B: Logit analyses (p-values in parentheses below coefficients)

Caught = αt + β1VISIBILITY + β2AUDITOR + β3BIGADS + β4NUMINV + β5AMOUNT

+β6MISLEAD + β7STEAL + ε

Visibility Variable

PRESSINT ANALYST MV

INTERCEPT −2.4321 −2.3958 −3.9020

(0.0001) (0.0001) (0.0002)

VISIBILITY 0.0028 0.3762 0.1502

(0.0481) (0.1356) (0.0424)

AUDITOR 0.6959 0.6654 0.3815

(0.0123) (0.0158) (0.1465)

BIGAD 0.0335 −0.0011 −0.2788

(0.4678) (0.4990) (0.2805)

NUMINV 0.1013 0.0824 0.1462

(0.0356) (0.0656) (0.0117)

AMOUNT 0.1833 0.1934 0.0976

(0.0050) (0.0083) (0.1763)

MISLEAD 0.6302 0.6664 0.6902#p#分页标题#e#

(0.0251) (0.0192) (0.0437)

STEAL 0.6090 0.6272 0.6139

(0.0336) (0.0299) (0.0642)

Likelihood ratio 299.41 301.06 213.19

(χ2) (31.02) (29.37) (23.43)

Two-tailed p-value for INTERCEPT, one-tailed for other variables.

This table presents analyses of differences between firms for which fraud was identified (CAUGHT = 1) and those

for which it was not (CAUGHT = 0). Sample size for all analyses other than those including MV is 263. Seventy-five firms

are coded as CAUGHT = 1. Sample size for analyses with MV is 181. Fifty-four of those firms are coded as CAUGHT = 1.

PRESSINT is measured as the total number of articles by the press over the fraud violation period divided by the months

of the violation. Articles were identified using Factiva. ANALYST is an indicator variable coded as 1 if the firm is in the top

quartile of analyst following for the sample, 0 otherwise. Analyst following is measured at the last month of the violation

period and is from I/B/E/S. MV is the log of market value of the firm in billions. Market value is measured on the last day

of the violation period and is obtained from CRSP. AUDITOR is an indicator variable coded as 1 if the auditor changed

during the period of the fraud or in the following year. Otherwise, coding is 0. BIGAD is an indicator variable coded as

1 if the firm is in an industry that was in Advertising Age’s top 15 advertisers for 1985, 1990, 1995, and 2000. Otherwise,

the coding is 0. NUMINV is the number of persons involved in the fraud as cited in the AAER. AMOUNT is the log of

the sum of the dollar amount of the violations documented in the AAER. MISLEAD is an indicator variable coded as 1

if the violations on the AAER included a materially misleading public statement or report, 0 otherwise. STEAL is an indicator

variable coded as 1 if the AAER indicates management misappropriated funds as a portion of the fraud, 0 otherwise.

1024 G. S. MILLER

recurring authors will be more likely to provide original analysis with strong

information content. While the findings in table 4 suggest the authors of

recurring articles are more likely to provide original analysis, the market

response is statistically equivalent across these two categories.

The final column reexamines the response to the information source categories

with controls for wire service and recurring articles. The response to

articles relying on analysts is lower in magnitude and no longer statistically

different from zero, all other results are consistent with those previously

discussed. This provides further support for the contention that press reporting

is most useful when based on analysis not available through other

information intermediaries rather than rebroadcasting of information. It is

important to note that these tests are based on one day returns and thus are

designed to exclude the period in which the nonpress analysis was initially#p#分页标题#e#

provided (i.e., the day of the analyst report, auditor resignation, or lawsuit).

To the degree that the test design successfully excludes these events, it

tests only the importance of rebroadcasting—it does not examine whether

information from these sources had an initial impact on price.

As an additional examination of information content, I collect daily trading

data from the Trade and Quote (TAQ) database. TAQ data do not begin

until 1993 and are also more restricted in coverage than CRSP data, resulting